Today’s post is from a Zoom chat on September 21st, 2022 with Dr. Pamela Allen Brown, Professor of English, who discusses her previous and most recent work and shares her thoughts on what might come next.

For some introductory information, can you tell me a bit about your background—academic and otherwise? Where are you from? Where else have you taught, researched, et cetera?

I was a Cold War-era military brat. My father was an Air Force officer and missile engineer, my mom an ex-intelligence officer. I was born in Cape Canaveral, before it became Cape Kennedy. We moved around a lot. I lived on bases in Germany, Pennsylvania, Nebraska, California, all before sixth grade. And then we settled in Maryland. I’m pretty mobile, I would say, having lived for periods in Turkey, Italy, and the UK as well, but I’m a New Yorker now. I’ve lived in New York off and on since 1976. I lived in Manhattan and moved to Brooklyn many years ago. I’ve been in Brooklynite for a long time, and I live in Fort Greene right now.

This is my second career. There’s quite a number of us in the department who are second-career people. After college and then a period of wandering and working some very odd jobs, I eventually became a magazine editor in New York. I was in journalism for a dozen years, most of them as a senior editor at American Lawyer. This wasn’t your average trade publication, but a muckraking investigative journal at first; it was always an incubator for a lot of writer-editors who went on to places like the Wall Street Journal, the New Yorker, Reuters, and The New York Times. I also reported, but I was mostly a mentor of writers, and I was known for being the writerly one with a literary bent.

I had no legal background at all, and no interest in becoming a lawyer; and after working for some years I realized I’d had enough of journalism. When I made the decision to try for grad school in literature, I was thirty-eight. Getting into a top program at thirty-eight is a very unusual thing. And Columbia was welcoming, for a brief shining moment in the early 1990s. A couple of professors (including Jean Howard, who became my mentor) pressed the English Department to admit non-traditional students like me. Jean is a feminist materialist scholar and a well-known leader in the field of early modern gender studies. With her support, I got through and even won a distinction on my defense, which I did not expect. At Columbia at that time, the graduate admission policy was notorious: They admitted fifty master’s students, put them to work teaching writing, and then winnowed it down to twenty in the Ph.D. program, so thirty were cannon fodder. This is what we all knew. There was terrible competition, and you knew your closest friend in the MA program might be gone next year. That was very tense, and I had left a good job in journalism to go to grad school. If it didn’t work out. I knew I could have gone back to journalism, but I would be saddled with massive debt. Some people were funded, some weren’t, and I wasn’t.

It was a big risk, so even before I applied to Columbia, I spent a year as an adjunct to find out if I had any aptitude for teaching, while still working full time as a journalist. At 7:30 in the morning I taught in the remedial writing program at CUNY LaGuardia. The students had all failed out twice, and they had one more shot to stay in college. I thought, if I can get through this, then I will stick with the idea of going to grad graduate school. And I found it to be this really difficult, heart-rending because I had students who would say, “I couldn’t do my paper because my friend was shot yesterday.” I actually got some through, and they were able to stay in college. I was a novice, but I poured a lot of effort into it. I thought, this is really much more useful and fulfilling than editing, so I stayed in.

Columbia was very demanding for me: I hadn’t done academic work in many years. People were much younger, and much better trained in theory and academic discourse, but I had a strong imagination and an ability to meet deadlines. So I made it to the next phase.

Can you tell us about your previous work, particularly your book that came out earlier this year?

My dissertation became my first book. I planned it that way because I knew—with being older—I really needed something very strong, and I needed it right away. It was accepted and published in maybe the fourth year that I came to UConn. When I came up with the idea, I had been arguing with another graduate student. I have always been interested in satire and comedy, and I was taking an eighteenth-century satire course from Michael Seidel. We were arguing because the other student said women couldn’t be satirists: “It’s just not possible.” He was restricting satire to what he judged as canonical, that is eighteenth-century Augustan satire—Swift, Johnson. He just thought that is the only kind of satire there is. This is 1993 perhaps. I started arguing with him that satire could be popular. Satire doesn’t have to be written or literary/poetic. Obviously, there is satiric prose as well, but I was saying that you could even tell a joke and be satiric, and he was saying, “No, no, no, no, no.” There could be satiric songs, and they could be against men. And he said, “No, there is no anti-masculine satire because satire is always attacking from a position of power, and that’s why the male satirist is such a crucial figure. There are no women satirists.” We got pretty heated, but when I was arguing with him, it gave me the grit in the oyster that led to my book.

I started gathering anti-masculinist jest and humor, and I found a lot in plays. I found a lot in early jest books, the jest books became my archive, and that led to Better a Shrew than a Sheep. I got a grant to do research at the Huntington Library in California, and that was crucial. I basically transcribed or pulled out the meat from forty different jest books. Then I was able to correlate them and correspond them to scenes and moments in drama and also to the lived experiences of non-elite women. That became my dissertation, and I had several publishers interested. Cornell published it. It was Jean’s advice at every turn that got me going.

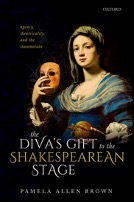

In the course of doing the book, I came across something a footnote in a piece by Phyllis Rackin, saying that foreign actresses may have influenced Shakespeare. She was citing Frances Barasch, who had done two articles on the famous Italian actresses. I read those, and I kept thinking about the charisma and talent of the first divas. Then I started finding and putting stuff in a pile, and then it became an article and then a book idea. This was 2003, and it’s twenty years later, right? I never thought it would take almost two decades from the initial idea. Progress was slowed down by my work on another project, a teaching edition of As You Like It, which I co-wrote with Jean Howard. But I really didn’t know how difficult it would be to do a cross-channel topic on the Italian divas, and really get Shakespeareans to listen, not to mention the readers for Oxford who sent me pages and pages of questions. I worked hard to make sure that it penetrated the anglocentrism of Shakespeare scholarship, and broke through institutional resistance to the idea that foreign artistry — by women players no less — influenced the all-male stage of Shakespeare, Webster, and Marlowe. I realized I had to build up my evidence to such a depth that it was unignorable, and I had to create a persuasive method for assessing the impact of female performers on playmaking across borders, extending from Italy, France, and Spain to remote England. I wanted to write it in such a way that reviewers weren’t put off by a huge mass of Italian plays, so I leaned on a varied archive of performance texts, including letters, poems, and accounts of actress acting, in Italian and French. This meant I had to do a lot of translating.

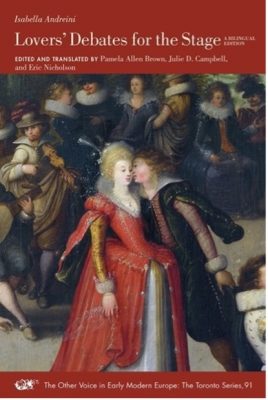

Speaking of divas on the stage and translating Italian, that segues into the bilingual edition of Lovers’ Debates for the Stage. You’re attending a conference with a special presentation on this in Chicago next week [the week of September 25th], correct?

Right. I have two co-editors: Julie Campbell and Eric Nicholson, and we worked on this for ten years. Julie and Eric are Italianists, so I’m the outsider. It came about because I talked to Eric, and then we brought in Julie, because I was translating so much for Diva’s Gift, and Isabella Andreini is the most-published Italian diva. There are a lot of Italian scholars and some English-language scholars who write articles and books on Andreini, so there’s a market for it. It’s also that this particular posthumous publication that her husband put together, who was her playing partner, is from both memory and documents that he compiled from their life together of lovers’ contrasti, or amorous debates. This was well known in that small world of Andreini people and commedia dell’arte people. Many had said that this should be translated, because it’s the only document that shows the arte Lovers’ techniques and what they talked about and how they spun out these dialogues on different topoi. It’s an important document for theater history. There’s nothing like it. We decided to call it Lovers’ Debates.

Julie is an organizer of the conference in Chicago, called Attending to Premodern Women, and this year’s theme is Performance. It perfectly slotted in with the launch of our book that just came out this fall. And about six months ago, a director got involved who is from The Shakespeare Project of Chicago. We are just so incredibly excited because they are memorizing and rehearsing a few dialogues we’ve translated, starring Isabella and Francesco. I feel honored and thrilled, and I can’t predict what they’re going to do, because there are two lovers in each debate. We have Cleopatra and Palamede, or we have Artemisia and Dioneo — thirty-one different pairs of famous men and women who weren’t necessarily paired in their histories. That makes the debates a kind of intellectual guessing game. In addition, instead of just having one Isabella and one Francesco, we’re having two Isabella actresses and two Francesco actors. To make it even more diva-like, one Isabella is also going to play a male role, because she often cross-dressed in the stage vehicles she wrote herself.

What are some of your current ideas or projects that you might like to share?

I’m working on a couple of talks about the racialized performances of the diva, who played a wide variety of roles, including African queens, gypsies, Arab astrologers, Turkish castaways, and cross-dressed Moors. In terms of creative writing, I have a poetry reading coming up with a collective called Treehouse, which formed during the shutdown to write together. In the past I have published only poetry, not prose, but right now I’m sketching my ideas for personal essays that try for the meandering eccentric freedom of Montaigne. Each would take up my own obsessions—a perception that you’ve mulled it over for so long that it would be easy to write. I realized I have a half dozen essays in mind, that I could just write without footnotes, without all that building of an argument in a more academic way. One is about women looking into mirrors in novels: I can’t start a book without coming across it; why is it always there? Another is my theory that often one animal or human in a film serves as moral center, arbiter of the good and true, often mutely, a role I call “the movie dog.” I also want to write about why women rush to clean up messes they don’t make, as if guilty of what I dub “the female stain.”

Do you have any writing tips for graduate students, especially on picking a project to pursue? How do you know when to pick up a project or when to set one aside?

You’ll need to find something that will sustain your interest over years, but you also need to face the indifferent reader and her fatal question, “So what?” Every field needs shaking up; you need an argument that will alter it for the better and be useful in a wider sense than getting the diss done. What do you care about and why should others care too? Make sure your central question reaches well beyond anything you can write about it in one book. In other words, don’t stop until you know it’s a big idea, then can cut off a doable part of it. The issue is when you have something and you think is big enough, but it isn’t. I would say that’s the real issue.

opportunity

opportunity