Ricardo Raúl Salazar Rey is an Assistant Professor at the Stamford Campus of UCONN. He visited the Folger with funding from the Early Modern Studies Group.

Since the Renaissance of the 12th century (the real one), one of the exhilarating drivers of human innovation has been the collective learning enabled by conferences/universities/libraries, where scholars gather to discuss and sharpen their ideas. However, as a nontraditional, single parent, early career academic at a regional campus, the requirements to find, apply, and attend such academic gatherings can be a bit daunting. When my eagle-eyed mentor Mark Healey pointed out that Jennifer L. Morgan, one of my academic heroes, would be directing a yearlong colloquium on Finance, Race, and Gender in the Early Modern Atlantic World at the Folger Institute, I really wanted to participate. However, with time running out to finish my application I got stuck. In what would become a theme, the UCONN liaison Brendan Kane and others kindly reached out and helped me to understand what/how I could contribute and shepherded me through the process.

With their guidance and after a lot of revisions my application was accepted, and I gratefully took the opportunity to travel to DC over the course of a year to meet and discuss my work with scholars from intersecting disciplines. Our meetings took place in the delightful physical settings of the Folger Library while utilizing their expansive academic resources. Beyond my excitement to join the colloquium, on a practical level, my participation was made possible because of the well-run generosity of the Folger Institute. They are flexible with financial aid and the accommodations provided were comfortable and convenient. The Folger is an encapsulation of some of what I find great in the United States. The people associated with the Folger believe in it as an institution and through them it has transcended the limitations of its original purpose and their intellectual diversity keeps its programs funky and fresh. If you ever get a chance to apply to any of the Folger Institute’s programs, do yourself a favor and go for it. If it doesn’t work, you can always email to yell at me 🙂

On an academic and interpersonal level, the way that professor Jennifer L. Morgan directed the colloquium was a triumph. We had around a dozen participants, which provided plenty of points of view through which to examine the issues without becoming a cacophony. Discussions were robust and informative. The participants where at different stages in their careers and Jennifer modulated our points of view while not making a fetish of consensus. Bringing us into her selection process got solid buy-in for a mix of cutting-edge material tempered by underappreciated classics. The focus of both the readings and the majority of the participants in the colloquium fell within the Folger’s traditional remit of the British/Anglophone world, which provided productive points of contrast to my focus on slavery and freedom in Iberoamerica.

My interest and understanding of Iberoamerica is grounded in personal experience. I grew up on a farm in rural Guatemala and like most people who are exposed to pervasive and systemic governmental dysfunctionality I am fascinated by the social building blocks of good governance. Moving between El Tejar, Guatemala and Stamford, Connecticut I have come to understand that how a society works is largely the product of the narratives that frame what is right, wrong, and/or possible in the common imaginary. This is doubly true for early modern empires, where the coercive reach of the state was severely constrained by distance and the available technology. Just like good governance, gender is an immensely variable construct that I grew up thinking was set by nature/God. At 18, I left the farm and over the course of my travels and education it dawned on me that almost everything I knew about gender was false and much of it perniciously so. As a journeyman teacher and scholar, in my classroom and in my scholarship, I continue to confront my biases and blind spots and the colloquium was informative to say the least.

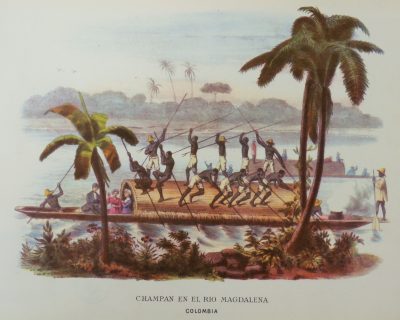

To set the stage, starting in 1492 the shattered pre-Columbian states became provinces of the expanding European empires. As European imperialism spread, the justification, form, and function of gender/family, community, trade, and polity changed radically, driven in large part by Africans and their descendants. Their participation was magnified in the tropical areas of the Americas where the original population was exterminated, few European peninsulares came and fewer survived, leaving Africans and their descendants to become the primary settlers of the Caribbean up to 1800. The rivers of humanity that disgorged into the Caribbean were there to produce tropical commodities (mostly drugs) to satisfy humanity’s growing addictions. Supplying humans with psychotropic substances was/is extraordinarily profitable, making the islands of the Caribbean the most valuable land of the Americas for European empires. In order to understand the lives of the people in these imperial zones, it is useful to conceptualize metropolitan policy as guided by imperial patterns of accumulation and limited by the infrastructures that made them possible.

Over the last decade, I have painstakingly tracked down, transcribed, and reassembled 54 legal cases spanning from the first half of the sixteenth century to the War of the Spanish Succession (1700-1715). They show all the brutality inherent in a slave-powered empire of conquest complicated by the House of Hapsburg’s self-conscious attempts to consolidate its power by providing Catholic buen gobierno, through an ecosystem of interdependent, yet mutually supervising, institutions. Exemplifying the tension between social cohesion and exploitation is the life of Juana de la Rosa and her children. Juana de la Rosa was born in Africa, but the exact place, even the region, is impossible to determine. During the 1670’s she was brought to the great Atlantic port city of Cartagena de Indias in bondage. In common with other talented and “lucky” people, over the next 20 years she became a successful merchant in alliance with her owners, the Copete family, eventually buying her freedom and that of her two daughters.

During the colloquium, I used what I’ve been able to find out about her life as a way to ground our discussions, comparing my interpretation of the documents to that of my colleagues, deepening my awareness of the special role of Afroiberian women in the shaping of the Caribbean world. Discussing the cases, I was able to appreciate the ways that Afroiberians exercised their agency, the way that gender was coded and how Afroiberians incorporated this code into their self-presentation in order to navigate the legal system. The legitimacy that the Spanish Empire enjoyed among the residents of its overseas possessions was a fundamental factor in its ability to control the vast territory it claimed, far beyond what could have been achieved with the limited military heft of the Iberian Peninsula. As a byproduct of this need for consent, Iberoamerica developed a legal system in which the enslaved could operate as independent agents separate from their owners. In the much more compact British Empire slavery and race combined to deny the enslaved the possibility of acting outside the control of their owners.

During the colloquium, our discussions engaged the roots, form, and consequences of the control enslaved African women and their descendants exercised over sectors of the urban economy in the Spanish and British Indies. While largely extractive, the system in Cartagena created spaces where semi-independent businesswomen like Juana de la Rosa could buy their own freedom, and then sometimes hire or buy other enslaved women. By then end of her life, she was an experienced factor working the Spanish Atlantic economy. As Juana de la Rosa achieved her freedom, and her daughters defended their freedom, we can see glimpses in the documents of their social networks—a cloud of people supporting and guiding their efforts to engage and direct the officials charged with enforcing the law. Africans and their descendants strategically allied themselves with the imperial government/Catholic Church to prevent those that would harm them from evading the rather short arm of the law.

The Spanish empire provided good governance not only because it accorded with its organizing philosophy but also because it was surrounded by powerful and voracious enemies. Early modern European empires, including the Spanish and British, engaged in cooperative competition as they fought to establish themselves as the preeminent brokers of the emerging global economy. Interlocutors and fixers arose in the Atlantic port cities of all empires, including cohorts of successful enslaved businesswomen. These women were sophisticated operators—literate, numerate, and legally savvy enough to effectively engage with the paper technology that powered early modern empires. The financial system and the legal ecology of each polity diverged and so depending on where they were enslaved, we see variations in the functioning and influence of women’s business networks.

My teacher, Daniel Lord Smail has convincingly argued that fitting together the legal systems that radiated out of these vibrant trading hubs requires a more “ecological understanding of the law.” In Smail’s conception, “we should treat the law as a coral reef” where “individual laws and statutes are ever so many calicle-forming polyps, gradually assembling a structure that is both living and dead.” Law functions then as an organizing superstructure, “a habitat for an extraordinary diversity of practices and unintended functions that grow up in its nooks and crannies.”[1] Building on this conception, my first book argues that within the early modern Spanish Empire, such a legal ecology became a significant platform upon which Africans and their descendants navigated, negotiated, and contested their enslavement and manumission. In doing so, an emergent “black majority” affirmed their humanity, established their membership in society, and pushed back against the dehumanizing tide of racialized slavery.[2]

Tying back into the organizing ideas of the colloquium, the early modern Spanish Empire forged a broadly inclusive, hierarchical, and flexible understanding of race modulated by gender and potentiated by the emerging Atlantic economic system. For example, a person’s unfree legal status or African descent did not preclude them from forming state-sanctioned marriages under Catholic Iberoamerican law. Universally accessible marriage was a core organizing belief espoused by the church and state amalgam that held together the Spanish Empire. The Catholic Church in Cartagena promoted families as a means of righteous social control. Amidst the cases, we can see evidence for enslaved women leveraging this support to protect their families and develop their businesses, often one and the same. People married strategically, using their spouses to anchor themselves in the community. Legal stability gave Juana de la Rosa the chance to build her social capital, participate in established and self-reinforcing networks of knowledge and trust—the very building blocks of human society. Echoes of this same dynamic enabled me to find work and establish myself in a strange land and this same social dynamic guides my path today.

[1] Susan Unger, “Priorities of Law: A Conversation with Judith Scheele, Daniel Lord Smail, Bianca Premo, and Bhavani Raman,” Comparative Studies in Society and History (2017). [2] See the introduction in David Wheat, Atlantic Africa and the Spanish Caribbean, 1570-1640 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2016).