Kristen Vitale is one of the Early Modern Studies Working Group’s New Co-coordinators and received a travel grant last spring to conduct research at the Folger Library This past July I participated in the Folger Orientation to Research Methods and Agendas Skills Course. The Library hosted twenty-six scholars from around the world to develop “a set of research-oriented literacies,” navigate the archive, and enhance our understanding of early modern book history. I left the Folger with thorough knowledge of the promised objectives and so much more. I now have a better grasp on my intended thesis project, refined paleographic proficiency, and a range of research skills that will aid in developing my ever-looming dissertation. I also gained a number of professional and personal relationships which formed with such ease that I, along with many others, viewed our meetings as pure serendipity.

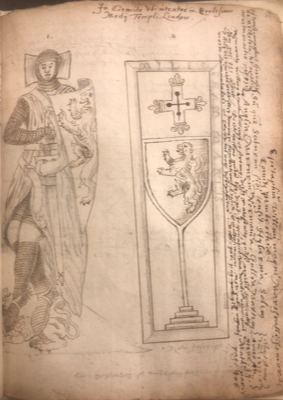

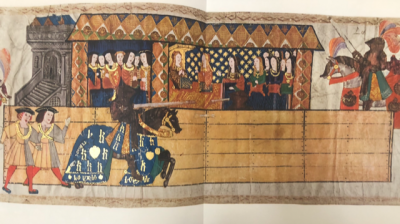

We entered the program with research topics that ranged from the Middle Ages to Milton. My work investigated the changing codes of conduct in the early Henrician tournament to gain insight into the transformation over time in the courtly spectacle. I had a pretty straight-forward objective when I began the program: explore and, in a way, prove that the cultural evolution of the tournament from 1485 through the Henrician Reformation

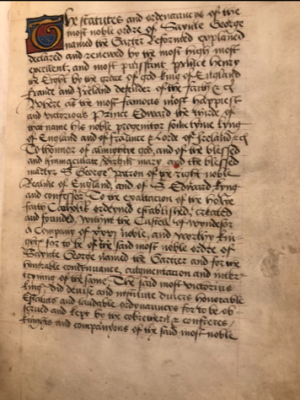

The statutes and ordinances of the Order of the Garter”

(c.1517-1559) contributed to my understanding of idealized codes of chivalric conduct and knighthood in the early modern world.

To further my newfound knowledge of Henrician chivalry, I headed to the Folger’s modern stacks and stared in awe at the historiographical compendium at my fingertips. I requested a range of secondary sources, such as Francis Henry Cripps-Day’s The History of the Tournament from England to France, Leon Gautier’s Chivalry, Diane Bornstein’s Mirrors of Courtesy, and a collotype reproduction o

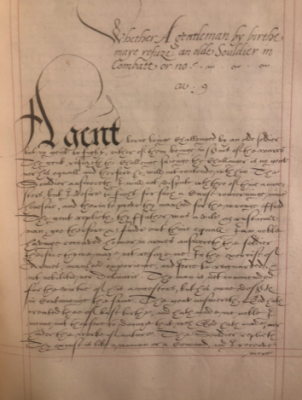

ng Room, I began to realize that the chivalric code itself changed between its inception to the sixteenth century. This realization was exciting, but it also complicated my entire theory. After a defeated sigh that was loud en

ough for those at my table to hear, followed by a collective muffled laugh, I accepted my first real lesson in the art of letting the sources guide my project.

My findings were only part of the successful trip; each day was packed with a number of fun and beneficial activities. These ranged from directions on how to handle, describe, and observe rare materials to guided instructions on how to use the Library’s search engine, Hamnet. Some events were interactive by breaking us into groups to explore and share our research, while others were instructional round-tables on the history of the book and bookmaking. One of my favorite activities was practicing paleography and

is an absolute must for scholars who are looking to advance

their academic career, expand their early modern network, entrench themselves in the wonder of the Folger archives, and discover a sense of their academic self, which the Folger staff and program participants (even if inadvertently) help you find.

T

T